|

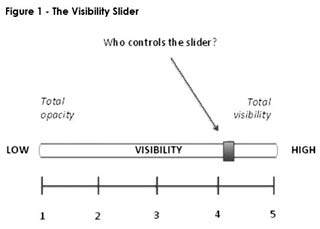

Assessing interdisciplinary academic and multi-stakeholder positions on transparency in the post-Snowden leak era Drawing on the debates in the ongoing ESRC-funded seminar series (2015-2016), 'Debating and Assessing Transparency Arrangements: Privacy, Security, Surveillance, Trust' (DATA-PSST!), we identify stances on transparency in the post-Snowden leak era held by participants. Participants comprise academics from diverse disciplines, and stakeholders involved with transparency issues. We advance an original transparency typology; and develop the metaphor of the Visibility Slider to highlight the core aspect of privacy conceived in terms of control, management, norms and protocol. Together, the typology and metaphor illuminate the abstract, complex condition of contemporary surveillance, enabling clarification and assessment of transparency arrangements. Keywords: privacy, security, surveillance, transparency, trust, Visibility Slider Introducing DATA-PSST! In June 2013, leaks from national security whistle-blower, Edward Snowden, revealed that intelligence agencies in the ‘Five Eyes’ nations (Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United Kingdom and the United States of America) are engaging in secret surveillance, comprising bulk data collection, storage and analysis of citizens’ digital communications, with seemingly unwilling complicity from global internet and telecommunications companies through which people’s data and communication flows. While sparking an intense and enduring public and political debate about state surveillance in some countries (especially the USA and Germany), responses in the UK were initially muted. Determining that we needed a better public debate informed by a wide range of academic disciplines and stakeholders concerned with transparency issues, our seminar series ‘Debating and Assessing Transparency Arrangements: Privacy, Security, Surveillance, Trust’ (DATA-PSST!), sponsored by the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC), was launched, with Vian Bakir principal investigator and Andrew McStay a co-investigator, among others. It aims to understand what different disciplines and stakeholders think of existing and desirable transparency arrangements in the post-Snowden leak era. The state surveillance that Snowden revealed takes place through multiple networks of mutual watching in a Big Data environment. Intelligence agencies’ mass surveillance relies on global internet and telecommunications companies (by bulk collecting data from companies’ servers, and by directly tapping fibre-optic cables carrying internet traffic); and it relies on citizens as they unwittingly offer up plentiful data about themselves through their everyday digital communications and digital footprint left across a surveillant assemblage. As such, our seminar series widens the debate from state surveillance to other forms of mutual watching, including peer-imposed (such as through social media) and commercial forms (for instance, free digital apps with unreasonable consent mechanisms for third-party tracking). Most importantly, we examine how different aspects of transparency affect questions of privacy, security, surveillance and trust. We chose these areas because the transparency practices that Snowden revealed violate privacy; are argued as necessary for security; engage in mass surveillance; and demand yet compromise social trust. To date, we have held three out of six seminars. The first, titled ‘Transparency Today: Exploring the Adequacy of Sur/Sous/Veillant Theory and Practice’, queried the extent to which theories on surveillance, social control and ‘sousveillant’ resistance (see Mann 2004) help explain contemporary transparency practices. Seminar Two debated ‘The Technical and Ethical Limits of Secrecy and Privacy’, asking not just what is technically possible regarding secrecy and privacy in the digital age, but also what is socially desirable. Seminar Three debated ‘Media Agenda-Building, National Security, Trust and Forced Transparency’, exploring the state’s attempts to manage public and political opinion of secretive national security and intelligence surveillance methods, and discussing the implications of mass surveillance for whistle-blowers, journalists, national security issues and trust in government. Participating academics are from a wide range of disciplines including Journalism, Media, Cultural Studies, International Relations, Politics, Intelligence Studies, Computer Science, Criminology, Law, Sociology, Business Studies, History, Nursing and Religious Studies. Importantly, participants have included diverse stakeholders involved with transparency issues, including data regulators, digital rights politicians, surveillance and encryption businesses, defence consultants, technologists, hackers, privacy activists and digital designers/artists. From these diverse perspectives, we have distilled various positions on transparency, drawing on these to build an original typology of transparency types. This raises issues of accountability and control, leading us to posit the notion of the Visibility Slider – our conceptual metaphor that encapsulates:

Together, the typology and metaphor illuminate the abstract, complex condition of contemporary surveillance, enabling clarification and assessment of existing and desirable transparency arrangements. This should prove valuable to the broad range of actors (politicians, regulators, activists, commercial organisations and journalists) seeking to communicate their position on contemporary transparency arrangements while also enabling the general public to better understand what is at stake. An initial typology: Three types of transparency McStay (2014), in a philosophical study of privacy, posits there are at least three types of transparency: liberal transparency, radical transparency and forced transparency. These are outlined below to provide a baseline for our analysis of our participants’ positions on transparency. A liberal transparency arrangement has two central values. The first advocates the opening up of machinations of state power for public inspection, rejecting any tendency towards uncheckability of power. The second is that law-abiding citizens should be able to live their lives free from the state’s prying eyes (assuming no wrongdoing is taking place). Today the over-arching principle is one of control so that the balance of power lies with a citizenry that: (a) has awareness and a strong say in state use of surveillance; and (b) personal choice and control over whether to be open or secluded with real or machinic others. This recognises that privacy comes to be by means of a wide variety of actors and processes (for example, peers, technology, laws, governments, public services, business interests), but that privacy protocol and guiding norms are most strongly influenced by the wishes of the citizenry and their individual personal choices. Although liberalism has multiple roots (such as notions of natural and civil rights and social contracts) its essential stress is on liberty as the avoidance of interference from others. This point is best expressed in John Stuart Mill’s (1962 [1859]) On liberty where he stresses the individual is not accountable to others as long as these interests do not concern others. This may appear individualistic and self-serving but Mill’s point is that the basis of a healthy society is predicated on free exercise of will, space for growth (of individuals and groups), and an unfettering of higher critical faculties. In contrast to liberal transparency that advocates only the opening of state power for public inspection, radical transparency opens up both public processes and the private lives of citizens. This position argues that if we were all more open, we would be happier. As the utilitarian philosopher Jeremy Bentham (1748-1832) suggests: A whole kingdom, the whole globe itself, will become a gymnasium, in which every man exercises himself before the eyes of every other man. Every gesture, every turn of limb or feature, in those whose motions have a visible impact on the general happiness, will be noticed and marked down (Bentham 1834: 101). The principle here is transparency for all, with mutual watching aiming to bring about a net utilitarian improvement (in terms of happiness and pleasure) for everyone. However, although radical approaches based on openness may have theoretical appeal, the practical implications are dystopian and chilling. The problem is that resistance to radical transparency is tantamount to guilt, rather than the exercising of choice and autonomy (as found in liberal arrangements). The emblematic mnemonic for this is: ‘Nothing to hide, nothing to fear.’ This also begs a fairly obvious question: what happens if one does not wish to participate in a radical transparency arrangement? Can some citizens participate, but others not? This raises the spectre of forced transparency – namely maximal visibility of all citizens (as in radical transparency arrangements) but without their knowledge or consent. Methods Our dataset comprises unpublished video footage of the first three seminar events (gathered with participants’ informed consent); summaries of the first three seminars recorded by participating PhD students; and a live project blog where participants publicly post their position statements (to steer debate in each seminar). While this includes 56 participants (41 academics and 15 stakeholders), certain important stakeholders have not participated in the seminar series despite being invited – notably the British intelligence community. However, its views are publicly available in reports published contemporaneously to this seminar series, which we have drawn on. These reports comprise:

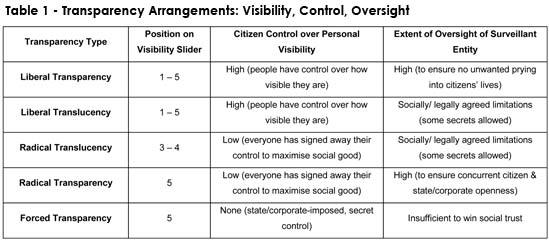

All of these reports carried interviews with senior members of the British intelligence agencies. Another important but absent stakeholder was the general public, but British and wider European public views have been incorporated through consultation of British opinion polls and an in-depth study (Pavone, Degli-Esposti and Santiago 2015, Ball, Dibb and Esposti 2014) on European public (including British) attitudes towards surveillance. With the tri-partite typology of transparency in mind, we combed through this material in a deductive and inductive manner, seeking to make use both of incoming data and pre-established theoretical positions in order to build on Layder’s notions linking theory and social research (1998). We examine the extent to which each participant’s position on transparency accords with the transparency typology outlined above. Importantly, however, we also identify positions that fall outside this typology, to see where the typology needs developing and refining. While space is a constraining factor, we have endeavoured to present the diversity of positions, as well as those that are most commonly held. Liberal transparency Stakeholders adopting a position of liberal transparency ranged from technologists to journalists, variously observing the need for public inspection of power to be directed at commercial and state entities. For instance, a technology standards developer states that commercial industry needs to be more accountable with what it does with people’s data: Commercial industry has run rampant with abuse of personal information, circumventing laws, being opaque about data sharing and surveillance practices. Much of this is a result of poor regulatory enforcement, the terrible accountability of government and dismal security oversight (Lizar 2015). Several British and European journalists stated that government should be challenged and held to account on national security and intelligence matters by the press, that with some British and global exceptions (Time Out, New Statesman, the Guardian, WikiLeaks) is frequently muzzled and asked to trust government. The long-standing nature of this poorly achieved liberal transparency arrangement is pointed out by Christopher Hird, former managing editor of the Bureau of Investigative Journalism and manager of Dartmouth Films (2015), who discusses the 1977-1978 ‘ABC trial’, which involved the incumbent Labour government’s use of the Official Secrets Act of 1911 to intimidate the British press from investigating the country’s signals intelligence operation: … the line pedalled by the government and in private briefings to the media was that these five were a threat to national security – a narrative reinforced by witnesses in the ABC trial (as it was known) not being identified. And further reinforced in my own case – as one of the people standing bail for the accused – by telephone calls from Special Branch to my employers (the Daily Mail) underlying the seriousness of the offences. The media consensus – until the collapse of the ABC case – was very much: if a Labour government says these people are a threat to national security, then we should trust them (ibid). Discussing the post-Snowden period, John Lloyd (2015), contributing editor, Financial Times; and columnist on Reuters.com, La Repubblica, Rome, queries how journalists can better hold intelligence agencies to account. Lloyd asks how far and on what grounds editors should accede: to requests by governments not to publish material which is said by the intelligence services to be harmful to national security and/or dangerous to intelligence officers? Third, as the intelligence world becomes more complex, how far are journalists competent to understand the criteria and processes used by the intelligence agencies – and thus how far should they seek closer relationships in order to grasp more fully the nature of the work, with the attendant danger that they would be consciously or unconsciously co-opted into the agencies’ world …? (ibid). Fresh in seminar participants’ minds was the recent example of the British press running what appears to be an intelligence agency-planted story on how Snowden’s leaks had endangered the lives of British spies (Greenwald 2015), this story timed to coincide with publication of the Anderson (2015) report that took a critical stance on British intelligence agencies’ mass surveillance. Indeed, while analysis of mainstream British press coverage of the Snowden leaks and digital surveillance shows a privileging of political sources seeking to justify and defend the security services, with minimal discussion around human rights, privacy implications or regulation of the surveillance (Cable 2015), opinion polls suggest that more of the British public than not are in favour of his leaks. For instance, a YouGov poll in April 2014 found that 46 per cent of British adults think it is ‘good for society’ that newspapers reported on the Snowden leaks, 31 per cent don’t know, and 22 per cent think it is ‘bad for society’ (YouGov 2014). Twelve academics (over a third of our academic participants) from different disciplines adopted a position of liberal transparency, examining the problems, and suggesting various routes, by which the surveillant state or organisation can be better held to account. Reflecting largely, but not exclusively, on British examples, five Journalism academics, one Media academic and two Intelligence Studies academics (from History and International Relations) suggest that liberal transparency would be better achieved through less state secrecy (for instance, within the military and within public inquiries) and less state/intelligence manipulation of the press (Bakir 2015b, Briant 2015, Dorril 2015, Keeble 2015, Lashmar 2015, Phythian 2015, Schlosberg 2015, Trifanova-Price 2015). This would not only lead to accountability of the surveillant state or organisation, but also create a better-informed citizenry with the resources to reflect meaningfully on what it wants its intelligence agencies to do. Looking beyond the state to the commercial world, an Organisation Studies academic calls for increased transparency of the relationship between state and private sector organisations involved in securitised data (Ball 2015); a Criminologist asks if authorities are collecting and examining white collar crime through Snowden-styled surveillance, or if this is protected under corporate privacy (Levi 2015); and an International Relations academic points to the need for stronger oversight mechanisms for private surveillant organisations: Concerns about geo-location services, excessively liberal terms and conditions, and an almost complete lack of access to information about how our data is repurposed seems to be consistently ignored in favour of ‘free’ applications and services and ultimately, profits. Essentially, if the law enforcement and intelligence communities require more oversight, certainly one could argue that the private sector does as well (Carr 2015). Finally, a Global Ethics academic posits a more direct role for academics in achieving liberal transparency: ‘We should be concerned about what lies in store for us as surveillance capacity reaches the next echelon. Our task as researchers is to assimilate what is already in full view and act’ (Wright 2015). That powerful surveillant organisations, be these state or commercial, should be held to account is therefore a widely held position, especially by the press and by academics studying the press and security and intelligence services. As for the ability to exercise personal choice about whether to be open or secluded with others, as the later section on forced transparency shows, this was also a widely held position. Radical transparency Only stakeholders directly linked to the state, the military or the intelligence agencies adopted a position of radical transparency, seeing this as necessary to achieve security (especially preventing terrorism) and finding this an acceptable position because the surveillance is subjected to appropriate oversight. Published reports from the Intelligence and Security Committee (ISC 2015a), the Interception of Communication Commissioner’s Office (IOCCO) (May 2015), Anderson (2015), the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI) (2015) and Simcox (2015) all commend the existing surveillance regime as lawful, necessary, and valuable in protecting national security and producing useful foreign intelligence. They also recommend changes to surveillance legislation (to enable its clarification and implementation); and greater transparency and oversight concerning intelligence agencies’ surveillance (to cultivate public trust in the surveillance). These views were echoed by two of DATA-PSST!’s stakeholder participants: an ex- military intelligence employee (Tunicliffe 2015) and a current UK data regulator (Bourne 2015). For instance, Tunicliffe (2015) argues that ‘The threats faced by the UK are genuine and in some cases publicly underestimated’; that ‘… there is an acceptance by many, although not all, that some level of surveillance is necessary’; and that ‘… whenever a successful terrorist attack takes place, … the focus is on asking why the security services failed to prevent the attack in the first place’. Tunicliffe argues that UK government agencies may sometimes be confused by complicated laws (such as those on intelligence surveillance) but ‘do not knowingly break the law’. He further states that they carefully protect ‘individual information’ due to its classified nature. He suggests that although we ‘require more transparent legislation and regulation’ to ‘achieve a balance’ between security and privacy, that ‘caution needs to be taken about constraining the agencies any further’. Similarly, Bourne (2015), group manager of policy delivery in the Information Commissioners Office (ICO), states: Many of those who care to think about state surveillance and the work of the agencies – most people don’t and why should they – would probably see themselves as the beneficiaries of state surveillance rather than as its victims. This is because they believe that the state – our state at least – is essentially benign and is acting in our interests: stopping the bad guys blowing us up or turning our critical national infrastructure off. In fact mass data collection – which is different to surveillance – has no impact on the vast majority of people. Have we really become less free or more psychologically inhibited as the result of it? No – this is a trade-off we are happy to make – we surrender some privacy for the protection of the state. A perfectly rational position based on trust. In fact our personal freedom is dependent on state surveillance. It may be possible to limit data collection and to target it more effectively. However, it is the ‘golden thread’ that connects information about people within a huge mass of data that can lead us to the bad guys. Those capacities are never going to be dismantled. We will never go back to collecting information only about known baddies because we don’t know who the baddies are, well not all of them (ibid). In seminar two’s discussion, Bourne further observes that nobody complains to the ICO about state surveillance, indicating, in his view, that they do not see it as problematic. Yet, a recent in-depth study, examining the European public’s perceptions of the privacy-security trade-off largely contradicts Tunicliffe’s and Bourne’s positions. This study on the European public’s attitudes towards security-oriented surveillance technologies (smart CCTV, deep packet inspection, and smartphone location tracking) across nine nations, including the UK, finds that few people are willing to give up privacy in favour of more security because, in fact, they want both (Pavone, Degli-Esposti and Santiago 2015: 133, Ball, Dibb and Esposti 2014). However, it also shows that the public are less likely to find surveillance as invasive of privacy the more effectively it generates security, putting the onus on the state and its security apparatus to prove that the surveillance regime is effective. Echoing the confusion of Pavone, Degli-Esposti and Santiago’s (2015) findings, an International Relations academic points to society’s apparent simultaneous refusal and acceptance of radical transparency, arguing for the need for stronger legal and normative oversight mechanisms to ensure that surveillance powers are not abused: At the same time as we object to the intelligence community’s access to our personal data, the parents of three young British girls who absconded to Syria protest that Scotland Yard should have picked up on Twitter messages that could have alerted them to their children’s plans. ... While we may wish law enforcement and intelligence agencies to be able to make full use of data to protect us, there remains a strong expectation that these powers will not be abused and it is clear that we do not yet have mechanisms in place to ensure that. Loopholes that have facilitated states spying on their own citizens contravene legal and normative frameworks and threaten to undermine trust in the state (Carr 2015). An Internet Ethics academic proposes that radical transparency, rather than being the state’s default setting, should only be occasionally used when the specific threat is high, and when public trust has already been built in the surveillers. He argues that for this model of surveillance to work, the state must be more transparent to establish citizen trust in its occasional choice to violate their privacy: A trusting relationship thus requires fidelity and transparency on the part of the surveillance organisation, and consent from data subjects. Participation in decision-making regarding appropriate forms of surveillance may also be required, in particular to establish appropriate limitations on transparency in the interest of operationally-required secrecy. When trust is breached, it must be clear who can be held responsible, and to what extent. Similarly, new or increasingly invasive forms of data analysis require notification within a trusting relationship. Systems and stakeholders that clearly establish responsibility before a system is implemented are, according to this conception of trust, more trustworthy. Each of these elements was lacking in the surveillance operations revealed by Snowden, indicating a lack of public good will which must be re-established if future surveillance practices are to be broadly justified (Mittelstadt 2015). While some academics point to the acceptance of radical transparency if there is better oversight, a Computer Engineering academic (Mann 2015) argues for better ‘undersight’ on the part of citizens. Mann is famous for developing ‘sousveillant’ technologies (for instance, body-worn cameras) to make the surveillance society more critically self-reflexive and hold surveillant power to account. Accepting the inevitability of ubiquitous surveillance, Mann suggests that this might be countered and disrupted through widespread adoption of ‘sousveillance’ – variously described as watching from a position of powerlessness, watching an activity by a peer to that activity, and watching the watchers (Mann 2004, Mann and Ferenbok 2013). In his position statement, Mann argues that more sousveillance would help hold the state to account (through undersight): … sousveillance (undersight) is often prohibited by proponents or practitioners of surveillance. I argue that this ‘we’re watching you but you’re not allowed to watch us’ hypocrisy creates a conflict-of-interest that tends to invite corruption (data corruption as well as human corruption). When police seized CCTV recordings from when they mistakenly shot Jean Charles de Menezes seven times in the head in a London subway in 2005, the police claimed that the four separate surveillance recordings were all blank (after transit officials had already viewed the recordings and seen the recordings of the shooting). Indeed the opposite of hypocrisy is integrity. In this way it can be argued that surveillance (oversight), through its hypocrisy, embodies an inherent lack of integrity. A society with oversight-only is an oversight on our part! (Mann 2015, italics in the original). While at first sight this appears to be a position of liberal transparency, in his discussion in DATA-PSST!’s first seminar, Mann explains his position further (also see: Mann 2004, Mann and Ferenbok 2013, Mann, Nolan and Wellman 2003). If sousveillance becomes widespread, so that everybody has the potential to watch and record each other (for instance, through camera-phones and social media), then this ensures everyone’s protection from abuse at the hands of power-holders and peers – a radical transparency position. Radical transparency, then, although seen as desirable for security, requires a high degree of accountability on the part of the surveillant organisation. No one – whether stakeholder or academic – thinks that the requisite level of accountability has yet been achieved. Forced transparency While certain types of stakeholder express a position of liberal transparency (journalists) and radical transparency (institutions linked to the state, military or intelligence agencies), a wide range of stakeholders think that radical transparency has been imposed on the public rather than operating with public consent – namely, that it is forced transparency. These stakeholders include the European and British general public, digital rights politicians, journalists, privacy NGOs, an encryption company, a technology standards developer and a digital designer/artist. Similarly, a wide range of academics hold that we are in a position of forced transparency. These various participants identify the range of problems involved in contemporary forced transparency arrangements imposed by commercial and state organisations, and posit a number of solutions. Participants identify two broad problems. The first is the absence of public consent, openness and choice in their surveillance (Feilzer 2015, Gomer 2015, Lizar 2015, McStay 2015, Mittelstadt 2015). For instance, Lizar (2015), a technology standards developer, argues that the problem is that commercial organisations operate through ‘closed consent’: …privacy policies online are closed because they are customised, with no common format, hidden in different places and often change without warning or a chance to consent to their changes. These policies are used to drive data surveillance practices that strip people of their data and privacy. Not only are people expected to agree to policies that they don’t read, are held to terms of services they can’t negotiate. People are expected to pay twice, once with their money and a second time with their data. The current system forces people to login to each service provider separately; forces people to spread personal information everywhere, share secret passwords and most abhorrently maintain personal profiles of personal information for companies. The systems of law that portend to give peoples rights are implemented to do the opposite (ibid). An Electronics and Computer Science academic highlights the lack of choice that people have in being commercially surveilled. He sees the web as ‘a surveillance tool’ funded by advertising, where: Networks of content providers, advertising brokers and advertisers allow private companies to record extensive amounts of web browsing history from individual web users which allow the compilation of ‘private digital dossiers’ that ‘allow the inference of many pieces of personal information; both in practice (for the purposes of delivering targeted advertisements) and in theory (were the data to be obtained by a fourth party and put to new uses)’. … Technological solutions to ensure privacy are doubtful: the technology that underpins this third party tracking is often either undetectable – the stateless ‘device fingerprint’ – or functionally ambiguous, by virtue of being the very same technologies that support end-users’ own legitimate aims – the stateful browser cookie that stores your shopping basket. These properties of the technology make it virtually impossible to determine the extent of the tracking that a particular user is subject to and limit the feasibility of technical countermeasures to block it. Given the ubiquity of third party tracking on today’s web, this provides a very real limit to the technical feasibility of online privacy (Gomer 2015). The second broad problem identified by participants is that forced transparency is an assault on civil liberties and digital rights on a number of fronts, including who is targeted, the citizen-state relationship, journalists’ ability to hold power to account, and the intrinsic value of privacy. On targeting, Tony Bunyan (journalist and director of Statewatch since 1991) argues that surveillance is overly-broad across the EU with many illegitimate targets, including the entire EU population, resulting from the EU state’s secret collusion with industry and a broad range of intelligence agencies (Bunyan 2015); and a Global Ethics academic points out the use of surveillant powers to target human rights defenders (Wright 2015). On the citizen-state relationship, Loz Kaye, (former leader the Pirate Party, founder of Fightback.Org UK) argues that blanket (rather than targeted) surveillance ‘fundamentally re-aligns our relationship with the state in a very dangerous way’ (Kaye 2015). Media and Intelligence academics point out the need for healthy distance between citizenry and governments; problems with what happens when the next government comes to power; whom incumbents will choose to share this information with; longitudinal technological change making even more private data digitally available; and mission creep (McStay 2015, Phythian 2015). Journalism academics (Keeble 2015, Lashmar 2015) and journalist Christopher Hird (2015) argue that forced transparency prevents journalists from obtaining confidential sources and hinders journalists’ work in effecting accountability over the state. Journalist John Lloyd argues that as the security state has hidden and lied about its surveillance, it has lost all rights to implied trust from journalists (Lloyd 2015). Pointing out the intrinsic value of privacy, one media academic argues that privacy is an ‘affective protocol’ (McStay 2015), and another points out that anonymity and privacy are vital for individuality and identity (Lin 2015). Participants identify four broad solutions to prevent forced transparency. The first solution comprises methods and mind-sets to block state and commercial surveillance of citizens. These solutions include using encryption software – as advocated by F-Secure, a pro-privacy Finnish technology company that makes ‘software that protects people’s data’ (F-Secure 2015); the development of ‘Positive Privacy’ – advocated by a technology standards developer – involving personal data control, withdrawal of consent to process, and the objection to profile (Lizar 2015); for secrets to be valued as spaces for radical dissent, that are facilitated through technologies and organisations such as TOR and the hacktivist group Anonymous (Birchall 2015); for the evolution of new journalistic methodologies such as face-to face interviewing of sources to avoid state electronic eavesdropping (Keeble 2015); and for European human rights legislation to be used against the surveillant state (Hird 2015). On this last point, one stakeholder has challenged British government surveillance legislation in the European Court of Human Rights: UK legislation to ensure that journalists can do their job of ensuring appropriate transparency of state and other agencies is not fit for purpose. In my capacity as Managing Editor of the Bureau of Investigative Journalism I am one of the people who has taken the British government to the European Court of Human Rights in an attempt to secure a ruling that the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act 2000 is a breach of the European Convention as it allows for mass surveillance of journalists’ (and others) communications (Hird 2015). The second solution to prevent forced transparency comprises awareness-raising of private data flows (Bakir 2015a, Devlin 2015, Feilzer 2015a, F-Secure 2015). For instance, a digital designer/artist advocates raising public consciousness of their own digital data flows through an artwork, ‘Veillance’, that he intends to create: The artwork consists of a web application and will employ ethical hacking processes to tap into users’ Facebook, Google and other data streams, re-appropriating their information, extracting moments where the invisible streams of data surveillance technologies intersect with their everyday practices. These largely opaque (i.e. not transparent) and invisible territories will then be rendered visible through the creative process, specifically through their re-appropriation and collation into a kind of visual diary assembled as a concrete poem in flux or a typographic mapping of the visible and invisible territories that increasingly constitute the spaces of our everyday lives (Devlin 2015). Stepping back from such interventionist approaches, a sociologist advocates differentiating the types of data mining practices that we want to subject to transparency and other regulatory measures, by distinguishing practices that trouble people from those that do not (Kennedy 2015). In a similar vein, but referencing wearable media such as fitness trackers, a Criminologist argues for better understanding of how the boundaries between private and public space and data have become blurred, so that individuals can better control information about themselves (Feilzer 2015a). The third solution comprises awareness-raising of digital rights. F-Secure (2015), the encryption company, believes that we should ‘fight a little bit harder for the rights of people in a digital society’. To that end, it launched the Digital Freedom Movement, ‘a group of people with a common understanding of how they think the digital society of the future could be’. The movement is based on the Digital Freedom Manifesto, ‘a crowd-sourced document from 2014, licensed under Creative Commons, that outlines how we believe governments, businesses and individuals should build a fundamentally digital society’. Widening this discussion of digital rights, a media academic suggests that we need political activism, framed not around privacy and individual rights but around questions of social justice – namely how surveillance architectures form part of a set of power relations that advance certain interests over others (Dencik 2015). The fourth solution comprises genuine public consultation, as advocated by Media and Criminology academics (Feilzer 2015b, Kuntsman 2015, McStay 2015). For instance, a Criminologist argues: Public opinion surveys suggest that public trust in government is low as far as the use and regulation of state mass surveillance is concerned. This seems to be true in the USA, the UK, and across a number of European countries. But public opinion does not seem to matter. It seems as if governments, rather than trying to manage public views are simply ignoring them. … It appears to me that government action is less about convincing citizens to give up their rights to privacy, etc., but rather to get them used to having their rights abused. So what current debates do not do is ask the question of how successive governments in a number of countries were able to ignore legal safeguards and the views of their citizens to mass surveil (Feilzer 2015b). To conclude, a wide range of stakeholders and academics hold that we are in a position of forced transparency. They see this as problematic in that it represents an absence of public consent, openness and choice; and an assault on civil liberties and digital rights involving inappropriate targeting, damaging the citizen-state relationship and journalists’ ability to hold power to account, and compromising the intrinsic value of privacy. Participants identify various solutions to prevent forced transparency, comprising methods and mind-sets to block state and commercial surveillance of citizens; awareness-raising of private data flows and of digital rights; and genuine consultation with publics. These point to participants widely desiring a liberal transparency arrangement – where citizens take control of, and make informed choices about, levels of their own personal visibility to others (as well as demanding strong oversight of surveillant entities). Extending the transparency typology While all three transparency types of liberal, radical and forced transparency were commonly expressed among DATA-PSST!’s participants, they do not exhaust the range of transparency types that were evident or that are possible. Below, we identify two further transparency types: radical translucency (expressed by certain stakeholders) and liberal translucency (a hypothetical possibility). We posit radical translucency as a variant of radical transparency. This retains a tendency toward openness, but the translucency aspect grants a modicum of secrecy to the surveillant entity and a modicum of privacy to the individual citizen. In this transparency arrangement, while there is official oversight of surveillant power there is also opacity regarding what is disclosed to citizens about specific operational details of surveillance. Furthermore, decisions on the degree of translucency of state and citizen are not decided by individual citizens, but are determined by societal agreement (potentially codified in laws and regulations). Stakeholders linked to the surveillant state have expressed the position of radical translucency. On granting a modicum of secrecy to the surveillant entity, the Simcox (2015: 14) think tank report on enabling espionage in an age of transparency advocates that we, the citizens, should be allowed to see the shape of the state secret but not the operational details: The concept of ‘translucency, not transparency’ has been suggested by Mike Leiter, the former head of the National Counterterrorism Center. With this, ‘you can see through the thick glass. You get the broad outline of the shapes. You get the broad patterns of movements. But you don’t get the fine print’. This is a realistic and workable concept by which to balance security and privacy concerns for the future. On granting a modicum of privacy to citizens, in the ISC (2015a: 32) report, the Government Communication Headquarters (GCHQ), Britain’s signal intelligence agency, argues that the main value of bulk interception lies not in the content of people’s communications, but rather in the information associated with people’s communications (what is widely termed ‘meta-data’, but what the ISC, below, refers to as ‘communications data’ and ‘content-derived information’): We were surprised to discover that the primary value to GCHQ of bulk interception was not in reading the actual content of communications, but in the information associated with those communications. This included both Communications Data (CD) as described in RIPA (which is limited to the basic ‘who, when and where’) … and other information derived from the content (which we refer to as Content-Derived Information, or CDI), including the characteristics of the communication. The Anderson (2015: 197) report notes that, given this situation, GCHQ recommends that there should be a new power to bulk intercept this meta-data alone, rather than (as present) all content as well; GCHQ argues that such an approach would intrude less into privacy. Notably, the choice of how individual privacy would be secured here is made by the state, not the citizen. Radical translucency is not just confined to stakeholders from the intelligence community, but is also found in the position statement of Planet Labs, a satellite company participating in DATA-PSST’s seminars. Planet Labs aims to see the broad outline of what humans do on the planet (namely, the physical impact of human activity), but not close up enough to reveal individual people, thereby granting a modicum of privacy to citizens: Planet Labs aims to take a complete picture of the Planet everyday, with a constellation of over 100 small satellites. The earth will be represented at a 3-5 meter per pixel resolution, allowing objects like cars, roads, trees and houses to be resolved. Planet Labs’ vision is to ‘democratize’ access to imagery of the earth, allowing all individuals, companies and organizations equal access to monitoring data about the Planet. We believe that this unique data set will transform human’s understanding of the planet, and create considerable public and commercial value – from monitoring deforestation and polar ice cover, to precision agriculture, mining and pipeline monitoring (Planet Labs 2015). Notably, the choice of how individual privacy is secured here is made by the corporation, not the citizen. While radical translucency was expressed by various participants, its liberal counterpart – liberal translucency – was not. Nonetheless, we develop this transparency type here, as it is a logical hypothetical possibility. We posit liberal translucency as a variant of liberal transparency. It advocates (a) official oversight of surveillant power although admitting of need for opacity regarding what is disclosed to citizens about specific operational details of surveillance; while (b) also enabling citizens’ personal choice and control over whether to be open or secluded with others. Discussion Through exploration of DATA-PSST! participants’ positions, supplemented by those of important stakeholders published contemporaneously to the seminar series (namely the views of the intelligence community and the general public), our initial typology of three types of transparency (liberal, radical and forced) was extended to encompass two more positions: liberal translucency and radical translucency. Further, the twin issues of citizen control and choice over their visibility exposure, on the one hand, and oversight of surveillant entities, on the other, run through all five of these transparency types. These are unpacked below. Transparency arrangements: Visibility, control, oversight The persistent issue of control and choice over an individual’s visibility exposure leads us to posit the metaphor of a Visibility Slider (see Figure 1). This encapsulates a continuum from total opacity to total transparency of individuals. When the Slider is set to ‘low’, the individual is in a position of total opacity – with the dominant mode being the locking down of information to keep it secret from others, including from the state or other surveillant organisations. When the Slider is set to ‘high’, citizens are in a position of total visibility. The questions this raises are: how are Visibility Sliders controlled, and to what ends? Our transparency typology offers guidelines here (see Table 1). Liberal transparency advocates personal choice and control over how open to be with real or machinic others. In other words, citizens largely manage their own Visibility Sliders themselves, deciding who sees what information about themselves. Although in practice, citizens’ potential for opacity remains dependent on the actions of a wide range of actors and processes (technical, industrial, legal, journalistic, governmental and fellow citizens), it is possible in principle, in this transparency arrangement, for citizens to set their Visibility Sliders to any position (1-5) in Figure 1. Citizens may want to be totally private, or they may be happy for the state to surveil them, but the point is that citizens can choose. Liberal transparency also advocates that powerful, surveillant organisations should be held to account to ensure no unwanted prying into citizens’ lives. A liberal transparency arrangement, then, advocates the opening up of state power for public inspection; and holds that law-abiding citizens should be able to exercise personal choice and control over how open to be with real or machinic others. Liberal transparency was a widely held position by DATA-PSST!’s participants. Liberal translucency is a variant of liberal transparency. Like liberal transparency, it advocates high personal choice and control about degrees of openness with others, and official oversight of surveillant power. However, liberal translucency also admits the need for socially or legally agreed limitations on such oversight, with opacity regarding what is disclosed to citizens about specific operational details of surveillance. Liberal translucency was not apparent in DATA-PSST!’s participants, and so remains a hypothetical position. In radical transparency and radical translucency arrangements, there is societal agreement about the norms and protocol surrounding privacy that tend towards total transparency – that is, the maximal opening up for inspection of both public and private processes for the general good. As these are socially or legally agreed norms, the citizen has low control over their own personal visibility, having given away their control to maximise social good (unlike a liberal transparency or liberal translucency arrangement). While radical transparency maximally opens up both public processes and the private lives of citizens to inspection, radical translucency retains this tendency toward openness but grants a modicum of secrecy to the surveillant entity and a modicum of privacy to the citizen. Again, decisions on the degree of translucency are determined by societal agreement (potentially codified in laws and regulations). In a radical transparency arrangement, the Visibility Slider would be set to 5 (i.e. maximum visibility), whereas in a radical translucency arrangement, the Slider would be set to somewhere between 3-4 (i.e. less than maximum visibility, for instance allowing some degree of personal privacy, but with a tendency towards transparency than opacity). Radical transparency is a position often adopted by DATA-PSST’s stakeholders directly linked to the state, the military or intelligence agencies. We can see the state urging us towards a radical transparency arrangement in its arguments that mass surveillance is necessary for our own security, that few people think or complain about state surveillance, and that most see themselves as beneficiaries rather than victims of state surveillance. The Visibility Slider is useful in this regard because it allows us to see state intentions to shift the visibility of citizens from opacity towards transparency. However, radical transparency demands not just maximum visibility of citizens but also maximum oversight of the surveillant entity. This prompts us to ask if there is sufficient oversight of surveillant organisations to generate public trust in such a radical transparency arrangement. Certainly, none of our participants – whether stakeholder or academic – thought that the requisite level of oversight has yet been achieved. Forced transparency is the pre-Snowden condition of surveillance, identified by critics since Snowden’s leaks. Like radical transparency, forced transparency demands that citizens are totally visible to maximise the greater good, but unlike radical transparency, a forced transparency arrangement operates without citizens’ knowledge or consent. The Visibility Slider metaphor, in foregrounding the question ‘who controls the visibility slider, and to what ends?’ draws our attention to the operation of surveillance at the network level. It helps us recognise that citizens are not in control of their personal Sliders, as their private digital communications channeled through corporate telecommunications devices, platforms and networks were secretly re-appropriated by the surveillant state, forcing maximum visibility on citizens (position 5 on the Visibility Slider). As the surveillant state in conjunction with telecommunications corporations secretly imposed such visibility on citizens, forced transparency lacks radical transparency’s underpinning of socially or legally agreed norms concerning citizen visibility. As identified by DATA-PSST!’s participants, the corresponding level of oversight of surveillant entities is insufficient to win social trust in such a transparency arrangement. Transparency today: Towards radical translucency Post-Snowden, the surveillant state appears to be moving from a position of forced transparency towards one of radical translucency. This advocates the opening up of both public and private processes for the general good, but with socially or legally agreed limits to the extent of oversight of the surveillant entity and the extent of citizens’ visibility. In principle, the limits imposed should not compromise the general good achieved by visibility. This is seen, for instance, in Simcox’s (2015) argument for citizens being shown only the overall shape rather than details of state secrets; and in GCHQ’s recent arguments to Anderson (2015) for being allowed to bulk collect meta-data alone, rather than also the content of citizens’ communications, this still enabling the achievement of better security. Post-Snowden, key surveillant corporations also appear to be moving towards a position of radical translucency. This is evident in PlanetLabs’ collection of planetary surveillance photographs, a utilitarian aim of the surveillance including contributing to the greater good (namely, better understanding of planetary processes), but with individual privacy secured by setting the resolution so that people cannot be identified. Similarly, radical translucency is being adopted by corporations that suffered reputational damage from Snowden’s revelations of their complicity in mass surveillance. These corporations now see commercial opportunities in privacy: for instance, in September 2014 Apple and Google moved towards encrypting users’ data by default on their latest models of mobile phones. A similar situation arises with developers of encrypted apps: for instance, popular messaging service Whatsapp announced in November 2014, that it would implement end-to-end encryption. Thus, US corporations appear to be moving to a transparency arrangement of radical translucency, as they simultaneously enforce the privacy of their customers (in regard to state surveillance) yet seek to make extensive use of non-personally identifiable data (for commercial ends). Critically, opacity decisions are primarily being made by corporations rather than citizens. Recognising that the criteria for a liberal transparency regime requires highly informed decisions by the citizen in regard to choice of hardware, software platforms and internet applications’ encryption; and recognising that citizens are unlikely to educate themselves to the requisite high degree of literacy on digital, privacy and surveillance matters; post-Snowden, corporations are acting to dictate privacy protocol. This quasi-paternalistic stance is a paradox given the publically stated libertarian impetus of these technology companies. Conclusion In conclusion, by focusing attention on issues of control and choice when it comes to visibility of self, the Visibility Slider is a useful conceptual tool. Its visual simplicity potentially makes it an impactful tool in relating the abstract and complex condition of contemporary surveillance back to the individual. As such, we envisage it enabling a range of actors (politicians, regulators, activists, commercial organisations and journalists) to better communicate their position on contemporary transparency arrangements (in terms of how much control over visibility of self they see citizens needing or wanting) while also enabling the general public to more easily understand what is at stake. Furthermore, when used in conjunction with our transparency typology (that presents a range of transparency arrangements of both self and surveillant entity, thereby raising the important question of oversight), the Visibility Slider helps illuminate contemporary modes of surveillance and identify current, and perhaps desired, transparency arrangements. This invites debate between civic actors on what (if anything) can or should be done about contemporary transparency arrangements. For instance, what is a suitable level of transparency and translucency for individual and state, and who should determine this? Are corporations best placed to determine, on their consumers’ behalf, what their levels of personal visibility should be? Are people sufficiently literate in digital, surveillance and privacy matters to make good choices? And do we have enough trust in the state and its oversight arrangements, to go along with its desire for radical transparency, or to trust its recent overtures towards radical translucency?

References

Note on the contributor Dr Vian Bakir is Reader in Journalism and Media at Bangor University, Wales, UK. She is author of Torture, intelligence and sousveillance in the war on terror: Agenda-building struggles (2013) and Sousveillance, media and strategic political communication: Iraq, USA, UK (2010). She is guest editor of International Journal of Press/Politics (2015) Special Issue on news, agenda-building and intelligence agencies, and co-editor of Communication in the age of suspicion: Trust and the media (2007). She is Principal Investigator on Economic and Social Research Council Seminar Series (2014-16), DATA-PSST! 'Debating and Assessing Transparency Arrangements: Privacy, Security, Surveillance, Trust': see: http://data-psst.bangor.ac.uk/

|