|

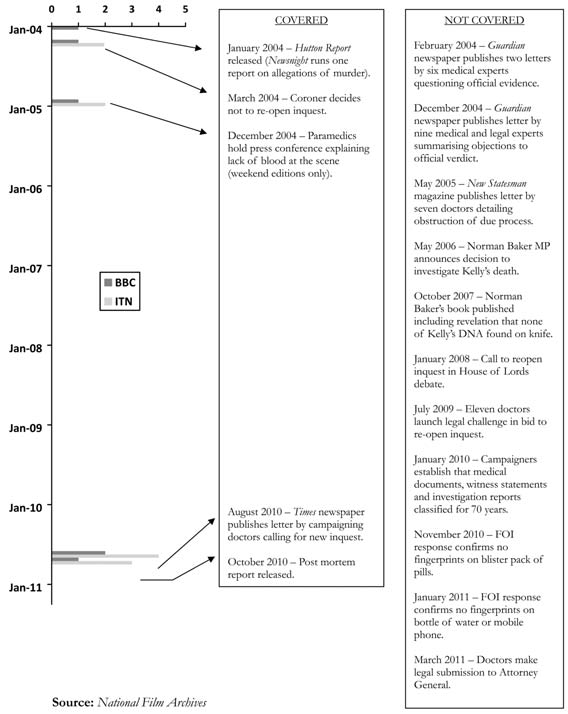

Covering the cover-up: The Hutton report in UK television news The Hutton report of 2004 was the outcome of an inquiry set up to examine 'the circumstances surrounding and leading up to the death of Dr David Kelly' (Hutton report 2003), a government intelligence analyst and biological weapons expert. Kelly was the identified source for an allegation made on BBC Radio Four's Today programme that sparked one of the most vociferous and public attacks on the BBC from a sitting government in its 80-year history. Whilst the report sparked allegations of 'whitewash', the controversy surrounding Kelly's actual death was to remain marginalised for the best part of seven years. During this time evidence has accumulated casting increasing doubt over the safety of Hutton's explanation. This paper presents findings from a study of television news coverage of the controversy between 2004 and 2010, based on qualitative and quantitative content analysis of news texts. Keywords: Hutton report, television news, cover-up, conspiracy theories, propaganda model Introduction Television news in the UK remains by far the most trusted and consumed news format – particularly the public service terrestrial outlets of BBC and ITN. The failure of these broadcasters to give due attention to conflicting evidence in the case of David Kelly raises important questions concerning the core objectives of the liberal democratic project. In particular, to what extent are the news media able to hold authority to account when non-media institutions of accountability fail to do so? Examining limitations in reporting an apparent ‘cover-up’ also presents a useful point of entry to the study of conventional media power in the digital age. It has been suggested that in an increasingly multi-platform, 24-hour news landscape, the capacity for elites to control information, determine the news agenda and define the framing of events has waned (McNair 2006). It is also suggested that the digital news landscape presents ever-growing opportunities for grass roots ‘citizen’ journalism to influence mainstream output (Thurman 2008). Such views are countered by those who argue that multiplying news outlets have fostered, paradoxically, growing homogeneity in content (Boczkowski and de Santos 2007). But it is the relative absence of certain reports from the mainstream agenda altogether that presents the most compelling challenge to contemporary liberal pluralist accounts. The controversy over how Dr Kelly died has, however, occasionally and briefly broken mainstream media barriers. As such, the case study allows us to assess both how the story was covered, as well as how it was marginalised. The latter question is critical to any attempt at grappling with perhaps the most elusive aspect of ideological power: the capacity to define the limits of public debate (Lukes 1997). But in researching stories left off the news agenda, a requisite challenge is to establish the grounds on which they should have been paid more attention, should such grounds exist. In other words, how can we be sure that the controversy was intrinsically worthy of greater exposure, or that its marginalisation was not simply an accidental by-product of randomness in the news selection process? In the analysis that follows, I attempt to show that marginalisation consisted at least partly in journalists’ active selection of evidence in favour of the official verdict, over that which undermined it. This was given added weight by interview findings which revealed that, overwhelmingly, journalists themselves maintained faith in the official explanation of death, and there is little basis on which to doubt their sincerity. It was this fact above all else which accounted for how they regarded the story in terms of news value. In effect, the newsworthiness of the story was intimately related to whether or not journalists subscribed to the official explanation of death, rather than the controversy’s inherent news value. Much of the following discussion is, therefore, concerned with epistemological considerations in attempting to understand why the official explanation of death was so believable, in spite of existing and growing evidence to the contrary. Within the sample population for content analysis, the criteria for selection were reports, studio features or interviews that focused either on the report itself, or on the death of Dr Kelly. The sampling period begins on the day of the report’s publication (28 January 2003) and continues to the campaigners’ final legal submission to re-open the inquest into Kelly’s death (25 March 2011). Interview respondents were sampled from the full range of journalists, news executives and sources who were engaged in the coverage of the report. In line with requests for anonymity, some responses are unattributed. Content analysis findings are discussed in relation to questions of how the story was both covered and marginalised. Interview findings are employed as a basis for speculating as to why this particular controversy was not afforded the weight of journalistic ‘outrage’ evident in the whitewash frame and countless other stories. The evidence points to an ideological rather than organisational filter which warrants further research. An establishment in crisis At the heart of the offending report on the Today programme at 6.07 am on 29 May 2003 was an allegation made by BBC journalist Andrew Gilligan. In a live ‘two-way’ discussion with the programme’s anchor, he asserted that the government ‘probably knew’ one of the claims on which it based its case for the invasion of Iraq earlier in the year was inaccurate. The implicit suggestion was that the government had lied in order to bolster support for a war that was by any measure the most unpopular since the invasion of Suez in 1956. The war certainly provoked unprecedented public protest and although it was notionally endorsed by both sides of the House of Commons, leading Labour and Conservative politicians detracted; the Liberal Democrat party opposed it outright; key Cabinet members resigned; and officials across the board voiced their discontent through various leaks and anonymous press briefings. In other words, the prospect of war drew lines both across and through the British establishment, a situation that was broadly reflected in the pre-war press (Freedman 2009). Although the war itself ushered in a degree of default consensus in media coverage (Lewis 2006), the immediate aftermath of regime change saw wholesale fractures re-emerge. The catalyst for this was the failure to find weapons of mass destruction (which provided the base justification for war) and the deteriorating security situation inside Iraq. Gilligan’s report coincided with both and as a result spread like wildfire across the global media. In the words of Alistair Campbell, the government’s chief media strategist speaking on BBC’s Newsnight on 28 January 2004, ‘this was a story that went right round the world. It was in virtually every newspaper in the world and we were accused of being liars’. Clearly, the stakes could not have been higher, nor could the controversy have involved more senior and powerful figures within the British state. In light of this, it is perhaps not surprising that the actual death of Dr Kelly – sudden and unnatural as it was – did not attract the spotlight of either the Hutton report or subsequent media coverage. Instead, the report served as a quasi-legal adjudication on the conflict between the government and the BBC. In the event, the government was broadly vindicated and the BBC wholly castigated, resulting in the unprecedented resignation of its two most senior figures. This provoked widespread allegations of ‘whitewash’ in television news programmes. But despite this spectacle of watchdog journalism, the news media widely accepted without question the official primary cause of death, to the neglect of evidence that had emerged during the inquiry which severely undermined it. This included the testimonies of two paramedics who had examined the body and maintained that levels of blood at the scene were inconsistent with death by arterial bleeding. A campaign was subsequently launched by a group of senior medical and legal experts who argued that evidence for the accepted cause of death was unsatisfactory. More importantly, they argued that the inquiry itself had not properly dealt with the cause of death and the government’s refusal to hold an inquest or release medical and police documents was tantamount to an obstruction of due process. What is most pertinent about the controversy that surrounded the Hutton report was not so much the ‘original sin’ of corruption (sexing up/lying), but corruption of the accountability system (whitewash/cover-up). This is what distinguishes coverage of Hutton from that of subsequent inquiries related to the Iraq War. It is also partly for this reason that the analysis starts, in a sense, at the end: the Hutton report marked a culmination of months of media fever over an establishment effectively at war with itself. The basis of cover-up It is important to stress that this study makes no assessment as to the validity of any positive arguments regarding the cause of Dr Kelly’s death, nor the wider question of whether it was suicide or murder. My aim is to consider the events purely in respect of what was known to journalists or could reasonably have been uncovered and to assess their responses in kind. In the following section, I draw particular reference to how television reported the conflicting medical evidence presented at the inquiry. But it is worth mentioning at the outset that apparent attempts to suppress information received no mention at all in the sample analysed. This is in direct conflict with journalistic discourse that tends to place significant weight on the news value of uncovering the cover-up. According to David Cohen, feature writer for the Evening Standard: It’s the ultimate in journalism to be able to bring down a Prime Minister and most leaders are threatened not by something they did wrong but by the cover-up. Almost always it’s the cover up. That’s what got Nixon. It is not within the realms of this discussion to provide a detailed exposition of all the available evidence pointing to a cover-up. But the following list serves as a sufficient basis for calling into question the failure of television news to hold this important aspect of the story up to scrutiny.[1] Tampering of evidence Shortly after Kelly’s body was found, his dentist reported to the police that Kelly’s dental records file was missing. According to the Attorney General, Dominic Grieve, who investigated the incident prior to rejecting campaigners’ submission for a new inquest: Dr Kelly’s notes should have been stored in a cabinet alphabetically but they weren’t there. The dentist looked through about fifteen notes either side of where they should be but they were not found. Two other members of staff also looked but couldn’t locate them.[2] Two days later, however, the dentist reported that the records were found ‘in their right place’. According to a Freedom of Information response by the Thames Valley Police, a total of 15 fingerprint marks were found on the file, nine of which were either unusable or eliminated to a member of staff.[3] That left six clear DNA fingerprint marks from unidentified persons. The Attorney General makes no mention of this crucial finding in his report, simply concluding that he is ‘unable to explain this aspect of the enquiry’. Suppression of evidence Despite releasing the post mortem report in late 2010, the majority of medical and police documents pertaining to Kelly’s death remain classified on the basis of protecting the interests of his family. These include photographs taken of the body at the scene where it was found, the full reports by forensic biologist Roy Green and toxicologist Dr Alexander Allan, as well as witness statements submitted in absentia by controversial figures including Mai Pederson, an alleged US army intelligence agent who was a close confidante of Dr Kelly (Baker 2007). It is a core contention of this thesis that given the conflicting and uncertain evidence surrounding the death of Dr Kelly – a senior public servant who suffered an unnatural death in extremely controversial circumstances – the public interest in disclosure would outweigh any emotional distress that it may cause for the bereaved. Disinformation In the summer of 2010 Tom Mangold, investigative journalist and long term critic of Kelly ‘conspiracy theorists’, added an online comment to an article he wrote for The Independent, explaining that the lack of fingerprints found on Kelly’s knife was attributable to DNA-resistant ‘gaffer tape’. The pruning knife used by David to cut his wrist was covered in gaffer-tape, as are many knives, to prevent the fingers slipping on to the blade and provide a firmer grip. It is almost impossible to retrieve finger prints from this kind of material (Mangold 2010). It was repeated as material fact by Andrew Gilligan in an article written for the Daily Telegraph (Gilligan 2010). However, a subsequent Freedom of Information response from the police confirmed that there was no such tape or any paraphernalia attached to the knife.[4] The fact that none of Kelly’s fingerprints had been found on the knife was established by Liberal Democrat MP Norman Baker four years earlier (Baker 2007). Whilst a host of unsuspicious variables might have caused the lack of fingerprints, the reporting of the alleged tape around the knife is revealing insofar as it is not attributed to any source and was later found to be erroneous. It is important to stress that the information presented above does not prove that evidence was tampered with or suppressed, or that attempts were made to disinform the investigation and the public. But they do point to the possibility of a cover-up and as such stand firmly within the bounds of acceptable journalist scrutiny. Indeed, it is the responsibility of fourth estate journalism to report not just what we know about a controversial case such as this, but also what we don’t know – provided the distinction is adequately qualified (see Reynolds v. Times). But apparent subversion of due process, excessive secrecy, and disinformation did little to prompt journalists’ concern. Clearly this starting position is an antagonistic one, at least in respect of the core subjects of my research: broadcast journalists. But although the analysis is focused on and critical of journalism, it does not follow that the problem is rooted in journalism alone. It is perhaps significant on this point that the medical controversy has not attracted the attention of some of the most radical and outspoken media critics. These include David Edwards and David Cromwell, whose Media Lens website (www.medialens.org) provides monthly alerts and dissections of media output, aimed at illuminating ‘a propaganda system for the elite interests that dominate modern society’ (Media Lens n.d.). A contained controversy An overview of the coverage suggests that whilst ITN outlets were more likely to cover the medical controversy than their BBC competitors, the story gained minimal coverage overall, surfacing briefly and sporadically in 2004 and then re-emerging in the summer and autumn of 2010 (see Figure 1). Figure 1: Number of reports referencing the medical controversy

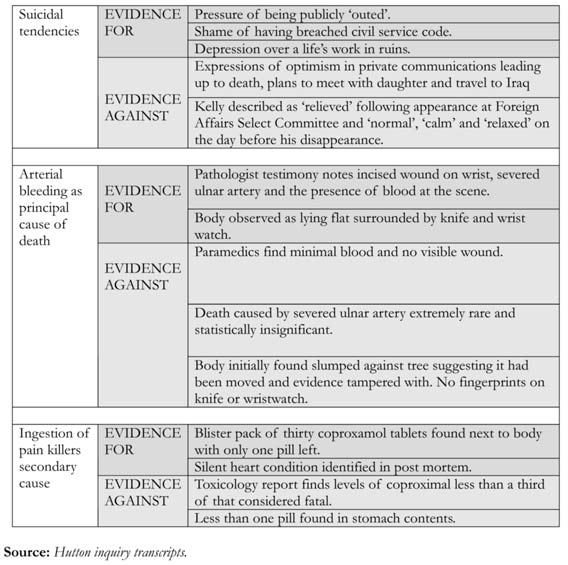

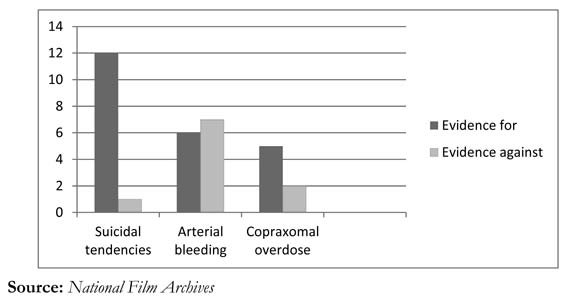

As noted above, the story’s lack of news currency was in some sense a function of its believability. That is, journalists tended not to view the controversy as a story because they did not give sufficient credence to the allegation of an unsafe verdict. There is little if any basis on which to doubt the sincerity of these views. But was the evidence in favour of the official verdict given more prominence in news reports than that which cast doubt over it? Table 1 displays an overview of the conflicting evidence presented at the Hutton inquiry and Figure 2 illustrates the number of times evidence for and against the official verdict was cited in the sample of news programmes analysed. Table 1: Conflicting evidence presented in testimony to the Hutton inquiry

Figure 2: Number of citations in news programmes of evidence for an against official verdict

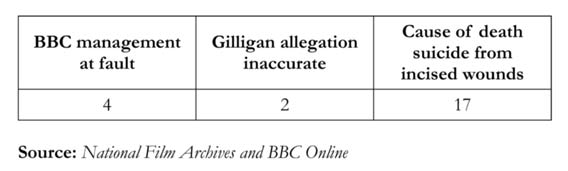

The data suggest that evidence for and against arterial bleeding as a principal cause of death was given more or less equal weight in news reports, and conflicting evidence over whether or not Kelly suffered an overdose was weighted in favour of the official verdict. The most significant finding, however, was that journalists overwhelmingly endorsed Hutton’s conclusion that Kelly was suicidal at the time of his death. In fact, conflicting evidence heard in relation to Kelly’s mental state was skewed against the view that he was suicidal. The only relevant witness who considered him to be so was a consultant psychiatrist who had never actually met Kelly, let alone interacted with him during his final days and hours. His testimony was based in large part on that of other witnesses, namely Kelly’s close family. But whilst they had spoken of him as ‘withdrawn’ and ‘subdued’, this was primarily in the context of the period leading up to his appearance before the Foreign Affairs Select Committee on 14 July 2003. Following that, Kelly’s daughter and son-in-law, with whom he was staying at the time, described his demeanour repeatedly as ‘normal’, ‘calm’, ‘relaxed’, ‘relieved’, and eating and sleeping ‘very well’ right up to the day of his disappearance. According to his sister, Susan Pape, who spoke to Kelly by telephone two days before his death: In my line of work I do deal with people who may have suicidal thoughts and I ought to be able to spot those, even on a telephone conversation. But I have gone over and over in my mind the two conversations we had and he certainly did not betray to me any impression that he was anything other than tired. He certainly did not convey to me that he was feeling depressed; and absolutely nothing that would have alerted me to the fact that he might have been considering suicide. Although Kelly’s wife had described him as ‘shrunk into himself’ and ‘heart-broken’ on the day he died, she did not consider him suicidal at the time, and stressed that ‘he had never seemed depressed in all of this’. Clearly then, the coverage of evidence relating to David Kelly’s state of mind before his death did not reflect the balance of evidence heard, and if anything, was inversely proportionate to it. This picture is even more acute if we consider the immediate aftermath of the report’s publication and the week of headlines that followed it. During this period, evidence in favour of Kelly being suicidal was cited seven times within the sample, whilst evidence against received no mention at all. Moreover, at every turn television news reported Kelly’s suicide by arterial bleeding as fact. Indeed, it was the one finding of Hutton’s report that was regularly stated in all outlets without any caveat or qualification (see Table 2). Table 2: Number of times key Hutton findings reported without caveat or qualification, 28-30 January 2004

Even when the medical controversy was covered, notably in August and October 2010, the issue was framed principally as a balanced debate between experts, effectively absolving journalists of their responsibility to question or challenge the official verdict directly. This was epitomised by the opening words of a report by Lucy Manning for ITV News (on 19 August 2010): Some, as the Hutton inquiry found, think David Kelly killed himself but some think the evidence just isn’t there, others that there was some sort of cover-up. The forum of expert debate enabled broadcasters to draw attention to their role as impartial arbiters. ITV’s News at Ten (also on 19 August 2010) ran a special feature in which a representative both for and against re-opening the inquest were given a platform to air their views. The introduction seemed to emphasise the broadcaster’s self-appointment as referee in this continuing conflict: ‘On tonight’s ITV News at Ten we hear from both sides in that debate.’ Whilst this framing resulted in a balanced presentation of for and against voices, it was a marked departure from the outspoken criticism levelled at the Hutton report within the ‘whitewash’ context. More crucially, perhaps, the expert debate was not quite as balanced in reality as suggested in news frames. In March 2004, Channel Four News pitched the views of medical experts against forensic experts but all of them considered re-opening the inquest to be both necessary and appropriate. On BBC’s Newsnight on 13 August 2010, the views of medical experts were juxtaposed predominantly with those of other journalists but even here, protagonists on both sides of the debate were often unanimous in calling for an inquest. One such supporter of an inquest was official pathologist Nicholas Hunt. He was by any measure the only medical expert in support of the official verdict who appeared in the media with any degree of prominence. This is not to say that there have not been other medical experts who have accepted the official explanation of death, either throughout the period since the Hutton report or at various points in time. But it does suggest that the debate was not as evenly balanced as it was framed in television news. Furthermore, much of the controversy is, in fact, based on forensic and procedural anomalies over and above the uncertain medical evidence. The reduction of the controversy to an expert debate therefore constitutes a significant aspect of containment in itself. Indeed, the very term ‘medical controversy’ embraced by television news, conceals the broader concerns of campaigners over an official cover-up.[5] In subtle and significant ways, even apparent journalist neutrality in the midst of this ‘debate’ was at times abandoned in favour of giving credence to the original verdict. The manner in which reports concluded was often particularly suggestive. In a way reminiscent of the immediate post-inquiry coverage, Liz McKean closed her Newsnight report on 13 August 2010 with a suggestion of what might have driven Dr Kelly to suicide: There can be no doubt about the calamitous effect on David Kelly himself – a man used to the shadows who found himself in the unblinking public gaze. Whilst the initial coverage in August 2010 was framed as a debate between experts, subsequent coverage, notably in October, was overwhelmingly given over to the release of the post mortem report and its apparent ‘debunking’ effect. This followed a statement in August released by Dr Hunt, re-emphasising that the death was a ‘text book’ case of suicide (Swinford 2010). Both the statement and subsequent post mortem were released in response to a letter by campaigners published in The Times on 13 August 2010 which had sparked the initial renewed coverage (Times 2010). But far from debunking the medical controversy, both of these responses raised further as yet unanswered questions. Specifically,

Whilst the bulk of coverage in August and October 2010 revolved around the official responses, none of it addressed the questions above, beyond inclusion of campaigner views in reports, often pre-empted by caveats such as this introduction by a Channel Four News anchor on 22 October 2010: The full post mortem was published in an attempt to end the speculation about how [Kelly] died. But the conspiracy theories persist. As well as implicitly dismissing the views of alternative sources, broadcasters also exaggerated the explanatory power of the post mortem, and presented its release as the end of secrecy itself in relation to Kelly’s death. Reports were typically introduced by anchors not with specific reference to the post mortem document, but simply to ‘previously secret evidence’ that had now been released. This declassification frame was epitomised by Simon Israel in a report for the Channel Four News on 22 October 2010 in which he declared: ‘Today that secrecy was lifted.’ Yet no mention was made of the approximately 900 police documents submitted to Hutton that remain outside of the public domain, along with the full toxicology and forensic biology reports. The basis of containment The analysis above suggests that the medical controversy’s failure to gain news coverage, particularly in the crucial post-report phase, was not simply the result of story selection randomness. Nor can it be dismissed as a reflection of the controversy’s relative news value (compared to the ‘whitewash frame’). Rather, it was at least partly attributable to a systematic tendency of journalists to overlook evidence contrary to the official verdict. The question remains why and how this neglect occurred. It was certainly not attributable to access restrictions or resource considerations. Throughout the hearings, all news outlets within the sample had dedicated reporters in attendance, with unfettered access to the testimonies and evidence presented. What’s more, the Hutton inquiry was in one way unprecedented in its openness – full transcripts of the hearings were published online as they progressed. Much of the contradictory evidence heard in relation to Kelly’s death was, therefore, easily accessible to all journalists, regardless of whether or not they attended the hearing. Nor can the neglect be attributed to a lack of voices questioning the official verdict. The inquest campaign is led by senior medical and legal experts, backed by a former front bench MP (who became a senior government minister in 2010) and represented by a leading human rights law firm.[6] Their distinction from ‘wacky conspiracy theorists’ was highlighted in a report on Channel Four News on 13 March 2004. But it did not prove sufficient to sustain coverage even when new information surfaced. In one interview response, Norman Baker highlighted the sheer lack of investigative impulse shown by the vast majority of professional journalists: If the entirety of Fleet Street has to wait until I submit a Freedom of Information request to demonstrate that there were no fingerprints on the knife allegedly used by David Kelly to kill himself, that’s a collective failure of Fleet Street not to find that out. Why is it left to one MP to find that out? That’s just one example. The question we are left with is why did journalists not consider the medical or cover-up controversy a story worth covering in depth? One explanation is adherence to a general consensus of what is acceptable copy for the daily news agenda, a so-called ‘safe zone’ of news. Criteria for inclusion within such a zone, if it exists, certainly do not preclude active and vociferous questioning of the government or indeed any notion of establishment elites. Journalistic outrage expressed through the whitewash framing of the Hutton report is one example. However, we can in this case at least point to a series of blind spots that gave rise to perceptions of the story as being too ‘unrealistic’ for the serious news agenda. A crucial question concerns which kind of evidence was assumed to be lacking and why? For many respondents, belief that Dr Kelly committed suicide appeared to be based on a rejection of the directly opposing conclusion that he was murdered. Much of this reasoning was based on the lack of apparent motive for murder, as investigative journalist Paul Lashmar explained: I just don’t see any evidence in the David Kelly thing that convinces me that someone decided to bump him off because it all came out anyway – well most of it. What did it achieve? This appeal to the lack of evidence for murder is perhaps an understandable response by those whose ‘gut instinct’ was to favour the official verdict. But, in effect, this put journalists on no firmer ground than those who consent to murder theories. Both groups based their beliefs in one possible outcome at least partly on the lack of evidence supporting the other. This reflected a common misconception that the controversy surrounding Kelly’s death revolved purely around a rejection of any possibility of suicide. There are certainly many who believe that Dr Kelly was murdered and even the most moderate of campaigners maintain that Kelly was highly unlikely to have died in the manner described by Hutton. But the legal campaign for an inquest rested on concern about the process which led to the conclusion of suicide. This somewhat moderate position certainly does not make great news copy as Dr Michael Powers QC, a leading voice for the campaign, intimated: From what I’ve seen the evidence of murder is really no better than the evidence of suicide. It may put me in a rather grey, less interesting and rather boring middle ground. But simply because you can’t prove suicide doesn’t mean to say that you can prove murder. They’ve both got to be proved positively and you may not be able to prove either positively. Although a belief in cover-up does not require subscription to any theory of intention, it does invite consideration of alternative possibilities. In this case, the notion of cover-up pointed to the potential that Kelly might have been assassinated by an agent of the state, or that elements of the state may have been in some way complicit in his murder. Such a notion is clearly at odds with a common assumption that state-sponsored acts of criminality or acts of terror do not exist, at least not on home soil. On occasion, the implication of cover-up was exaggerated so as to invoke an obvious aura of absurdity. According to Paul Lashmar: I don’t think there are MI5 or MI6 assassins wondering around Britain bumping off people who don‘t agree with the state, which is the sort of implication. This seemed to reflect an instinctive presumptive reflex amongst journalists against the counterfactual implications of cover-up, which made the official verdict simply more plausible. Such a reflex was articulated broadly by Robin Ramsay, editor of the online magazine, Lobster, and author specialising in the security state: Inside all our heads and inside the heads of editors is a notion of how the world works and if you pitch at them something which says your understanding of how the world works is false or inadequate they will reject it. In a way this is merely describing how a kind of intellectual hegemony works. It is the conventional view amongst political journalists in this society and political editors in TV stations and newspapers that the world is dominated by cock-ups and not by conspiracies. That’s their fundamental view. Their second fundamental view is the rest of the world’s secret states may murder and torture but ours doesn’t. These are almost bed-rock beliefs. Perhaps the most significant force of containment in this context is the campaign’s susceptibility to the label of ‘conspiracy theory’. This taboo, which operates within journalist and academic circles alike, has some sound basis. It discriminates against conjecture often associated with tabloid sensationalism or internet subcultures that respond to official secrecy with unfounded and empirically baseless reasoning. It has also provided the foundation for racist and extremist ideology upon which acts of terror, genocide and ethnic cleansing have been predicated. This rightly cautionary approach, however, has led to an outright rejection of the idea that particular groups of powerful people might make ‘a concerted effort to keep an illegal or unethical act or situation from being made public’.[7] The problem amounts to an ‘intellectual resistance’ with the result that ‘an entire dimension of political history and contemporary politics has been consistently neglected’ (Bale 1995). This research uncovered a similar resistance amongst some respondents who simply dismissed any notion of cover-up with characteristic derision, employing words like ‘nonsense’, ‘insanity’ or ‘laughable’. Others expressed a reluctance to engage with evidence of cover-up because it appeared to be based on anomalies which can be manipulated to fit any theory. For those that did endorse the notion of cover-up in this case, it tended to be framed as a manifestation of ‘secrecy for secrecy’s sake’; a culture of information control so pervasive as to be employed even when it was not necessary. According to ITN’s chief correspondent Alex Thomson, the sheer obviousness of the state’s behaviour made the idea that it was anything other than bureaucratic ‘neurosis’ somewhat incredulous: If there had been a cover-up it is hard to imagine a state behaving in a more obvious way of sending the signal that there had been a cover-up...Does the obsessive secrecy and general kind of official neurosis exhibited by the Ministry of Justice and many other officials in this case tell us anything about the potential for conspiracy? I think probably not. Does it tell us that we’re a pretty sick state when it comes to secrecy for secrecy’s sake? Absolutely… when I asked the Ministry of Justice to simply answer the question why it has taken nearly a year to get the papers put in the public domain, it took five press officers and nine weeks and I still didn’t get an answer. Part of the problem is perhaps a tendency to view the notion of conspiracy in totalising terms and overlook the degree to which information is controlled within the state. In its common association with the term conspiracy, a cover-up is often assumed to involve the knowledge and co-operation of a large number of state actors, sometimes extending to journalists themselves. Norman Baker’s own estimation was that those with first-hand knowledge of all information pertaining to Kelly’s death are probably ‘very, very few in number’. Whilst the perceptual blind spots identified above clearly played a central role in keeping the controversy out of the news spotlight, we cannot discount the possibility that they were aided by instrumental factors – namely official source strategies. Part of the problem is an apparent imbalance in relations between journalists and security state sources. It is manifest in an instinctive deference that one journalist (who wished to remain anonymous) alluded to in reflecting on his own experiences: You have to police yourself very carefully when you do come into contact with them. There is a bit of a thrill – we’ve all been brought up on James Bond. We were taken in to see ‘C’ at MI6 and you have lunch and you chat away and you’re in the heart of this building that nobody goes into and it’s absolutely thrilling and fascinating. Overly friendly relations between journalists and security state sources manifest not only in an unchallenged platform for ‘approved’ stories, but also in a mechanism by which competing stories can be silenced or modified. According to Robin Ramsay: When I was working at Channel Four news on the Colin Wallace story [involving allegations of state corruption by a former army information officer during the 1970s], there were several attempts by journalists on the ITN staff to dis-inform the investigation that we were doing because their friends, their allies in the secret state whispered in their ears and said: ‘These chaps are off on the wrong lines why don’t you steer them towards X.’ Some respondents, including Norman Baker, went as far as to suggest that some of these contacts were not just friendly but paid employees of the security services: ‘If I had to guess I‘d say there’s probably someone in every paper and there’s probably a retainer paid but that’s my speculation.’ What seems certain is that journalist-security state links are entrenched and historically evolved and raise profound questions for their role in holding institutions of authority to account (Keeble 2000). It was not after all the Prime Minister or, indeed, the government that were at the centre of the controversy, but the security state – by its very faceless nature a much more difficult entity to challenge and scrutinise. Whether or not secret forces worked to keep the controversy off the news agenda is unclear. But in any case, it was unlikely to have been as significant as another key aspect of official leverage: bureaucratic delay. One of the most powerful tools at the disposal of official sources is the timing of announcements. In this case, a succession of bureaucratic delays in response to submissions by campaigners has had two significant consequences. First, it has limited the amount of evidence available in respect of Dr Kelly’s death. As Dr Margaret Bloom, a specialist in coroner’s law, observed: I think that we might have been in a very different position had an inquest been held timely back when further investigations could have been made with a much closer time juxtaposition. Second, the lapse of time has fostered a degree of media exhaustion. In the words of acclaimed investigative reporter Phillip Knightley: ‘The whole edge goes off it, the whole urgency disappears and vanishes into a bureaucratic entanglement that the story never gets out of.’ Such sentiments endorse the view that the ‘whitewash frame’, in its saturation of media headlines, had simply exhausted coverage of the Hutton report per se. In this sense, the dynamics of the news cycle demanded not so much new evidence, as a new topic altogether. By the time the medical controversy began to resurface in television news during 2010, according to one senior BBC news editor, ‘there was an attitude of “well, you know, we’ve done that and the story is over.”’ Conclusion Analysis of content showed a sustained lack of television news attention to the controversy surrounding Kelly’s death, both in terms of story selection and framing. This consisted in an active endorsement of evidence in support of the official verdict (and to the neglect of the contrary); a relatively extreme adoption of impartiality codes that distorted and relegated the controversy to an ‘expert debate’; persistent favouring of official responses over new evidence produced by campaigners; and the failure to draw attention to existing evidence that continues to be withheld, and to the various anomalies that point to an official cover-up. Thus, even when the controversy briefly surfaced in television news, journalists on the whole paid deference to official dicta. This was particularly noticeable in the introductions and conclusions to reports where framing was at its most explicit. The associated advantages of ‘primary definition’ (Hall 1978) were manifest in an uncharacteristic benefit of doubt afforded to official sources both in accepting the verdict of suicide, and in rejecting a notion of cover-up. It reflected a common underlying faith not in politicians or the powerful as such, but in the institutions and procedures that legitimate their power, including the media itself. The obvious exception to this was the ‘whitewash frame’ which poured scorn on the Hutton report and heralded an unprecedented media critique of the inquiry process. But this critique was largely implicit, and unrelated to the more obvious failings of due process that were evident in the way Hutton reached his verdict of suicide. And in one important sense, the ‘whitewash frame’ served as a spectacle of accountability in positioning journalists as taking up the reins of accountability. This type of spectacle is not captured by radical functionalist models of media performance. This is partly because the controversy featured unrivalled elements of elite dissent not accounted for in the ‘propaganda model’ (Herman and Chomsky 2002), according to which splits in elite ranks are only marginal and limited to questions over ‘tactics’ rather than ‘goals’. Other accounts, known collectively as ‘indexing’ theory, allow for a broader range of elite responses but nevertheless hold that contestability in the media is ‘tied’ to elite interests (Livingston and Bennett 2003; Hallin 1986). In the case here, the extent of elite dissent suggests that indexing models would have predicted greater attention to the controversy than that which actually surfaced. In the event, marginalisation might well have been aided by various official source strategies, including bureaucratic delay, disinformation and suppression. But above all, it was the product of cultural and intellectual blind spots which left the commonly held impression that the medical controversy was both ‘unrealistic’ in its implications, and lacked sufficient evidential basis. The result has been a collective ‘don‘t go there’ attitude which, although not rooted in or limited to journalism, presents question marks over journalism’s capacity to stand as a last line of public interest defence. If there is a failure at the procedural level of justice we depend on journalists to uncover that failure, bring it to light, and either directly or indirectly provide the conditions for redress. This is not to suggest that either procedural or journalistic failure is beyond repair or that the controversy has been irrevocably marginalised. The fact that the story continues to recur in the mainstream media, however fleeting and sporadic, is an indication of its endurance and the potential for retrospective accountability. In the summer of 2011 however, the Attorney General rejected a final legal submission by campaigners to re-open the inquest into Kelly’s death. At the time of writing, it is unclear as to whether the decision will be challenged by judicial review. Notes [1] A cursory examination suggests a similar failure across the national press with the exception of the Daily Mail and the Mail on Sunday which has regularly supported the campaign for a new inquest and featured articles detailing alleged corruption in the investigation and inquiry. [2] Dr David Kelly, AttorneyGeneral.gov.uk. Available online at http://www.attorneygeneral.gov.uk/Publications/Documents/Annex%20TVP%206.pdf, accessed on 31 August 2011 [3] Disclosure log item: Investigation into the death of Dr David Kelly, 13 May 2011, ThamesValley.police.uk. Available online at http://www.thamesvalley.police.uk/aboutus/aboutus-depts/aboutus-depts-infman/aboutus-depts-foi/aboutus-depts-foi-disclosure-log/aboutus-depts-foi-disclosure-log-investigate/aboutus-depts-foi-disclosure-log-item.htm?id=175657, accessed 31 August 2011 [4] Disclosure log item: Investigation into the death of Dr David Kelly, 8 March 2011, ThamesValley.police.uk. Available online at http://www.thamesvalley.police.uk/aboutus/aboutus-depts/aboutus-depts-infman/aboutus-depts-foi/aboutus-depts-foi-disclosure-log/aboutus-depts-foi-disclosure-log-investigate/aboutus-depts-foi-disclosure-log-item.htm?id=168251, accessed on 31 August 2011. [5] With this caveat in mind, and for the sake of clarity and consistency, I continue to employ this term to denote the broader controversy over the official verdict [6] See http://www.leighday.co.uk/news/news-archive-2010/leigh-day-co-partner-invited-to-join-foreign, accessed on 21 March 2011 [7] Definition of cover-up from Merriam-Webster.com. Available online at http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary-tb/cover-up, accessed on 15 March 2011 References

Note on the contributor Justin Schlosberg is a visiting tutor and PhD candidate at Goldsmiths, University of London. His primary research interest is in the relationship between the media and justice and his thesis is tentatively titled 'Covering crimes of the powerful: Media spectacles of accountability'. He has recently worked on research projects for the Open Society Foundation and Media Trust examining the state of digital media and local news in the UK. Email j.schlosberg@gold.ac.uk |